The Merry Wives of Windsor

A Midsummer Night's Dream

The History Plays

Love's Labour's Lost

The Tempest

Shake-speare and Magic

The Sonnets and the Occult

The Plays and the Occult

William Stanley and Occult Influences

William Stanley and The Tempest

Sources of The Tempest

The plays of Shake-speare concern William Stanley's life and family, certainly more than any other candidate. It is most necessary to point out that the plays concern Stanley not from some decoding of their content only possible for those "in the know" or because of some strange and unique interpretation of their subject matter. The plays concern Stanley more, far more, than any other candidate in their obvious and generally agreed upon subject matter.

The proponents of Oxford, Shakspur, Bacon, and so on, may well explain each and every instance of the Stanley connection as if it supports their candidate. "Bacon was his lawyer!", "Oxford was his father-in-law!", "Shakspur was indebted to his brother!" In the long run, what they have to explain is Stanley, again and again and again.

One of the most famous of legends regarding Shake-speare is that he was arrested for poaching deer. Another is that he was asked by Queen Elizabeth to write a play with Falstaff in love. There is no direct evidence to support either of these legends, but both relate to the play The Merry Wives of Windsor. In this play, Shake-speare brings back the popular characters from his history plays: Shallow, Pistol, Nym, Mistress Quickly, and above all, Sir John Falstaff. The play opens with Justice Shallow promising to bring a case before the Star Chamber (the judicial role of Elizabeth's personal advisors, the "privy council") for riot against Sir John Falstaff's men for, among other things, poaching deer.

An obvious problem with connecting this with Shakspur is that there is no record of Shakspur ever being arrested for or even accused of deer poaching. Less obvious but ultimately more damning to that theory is that an incidence of deer poaching by a common youth in Stratford-on-Avon would hardly be cause for a hearing by the Star Chamber, a very high-level council designed to address issues of riot and issues pertaining to the aristocracy. We could say that the poaching incident did take place but the records were lost, that Shake-speare was referring to it, and that he deliberately exaggerated it into a riot and Star Chamber hearing. But we could say lots of things, and generally must, to support any kind of Stratfordian candidacy. The case is much more simple and direct with the Earl of Derby.

The Merry Wives of Windsor was licensed in 1601 and first appeared to the public in a corrupted Quarto edition (possibly concatenated from actor's play copies) published in 1602, an edition prefaced with the information that the play had already been performed before the Queen:

Entermixed with sundrie

variable and pleasing humors, of Syr Hugh

the Welch Knight, Iustice Shallow, and his

wife Cousin M. Slender.

With the swaggering vaine of Auncient

Pistoll, and Corporall Nym.

By William Shakespeare.

As it hath bene diuers times Acted by the right Honorable

my Lord Chamberlaines seruants. Both before her

Maiestrie, and else-where.

The play opens with a pompous and enraged Justice Shallow promising to bring a "riot" (an illegal act of multiple individuals) to the attention of the council of the Star Chamber:

Shal: Sir Hugh, perswade me not: I will make a Star-Chamber matter of it, if hee were twenty Sir Iohn Falstoffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow Esquire.

...Shal: The Councell shall heare it, it is a Riot.

...Shal: The Councell shall know this.

...Shal: Knight, you haue beaten my men, kill'd my deere, and broke open my Lodge.

...Act I scene i (First Folio text)

About the time this play was first performed and published, in fact in 1602, an action that had been pending for some years was brought before the Star Chamber by one Justice of the Peace Stephen Proctor against officers of Will Derby. Proctor was a neighbor to Derby's Yorkshire estate, and in the surviving records of the action we read that Derby's side refers to Proctor as "puffed up with vain glory". Proctor, for his part, claims that the Earl of Derby's men performed many of those actions attributed by Justice Shallow to Falstaff including assaulting his men and killing his deer [1].

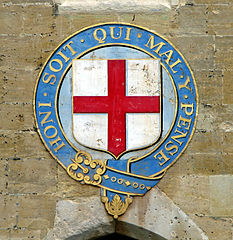

Both to fully appreciate the play The Merry Wives of Windsor and to understand its context, we need to understand some things about British chivalry, because the final act of the play is clearly concerned with England's highest order of chivalry, the Knights of the Garter. While the name sounds odd to modern ears, the garter itself apparently takes its origin from a garter worn by Knights below the knee to secure armor to their leggings while on horseback. Queen Elizabeth, following the tradition founded by Edward III in 1348, kept invested 26 Knights of the Garter, no more, no less. The death of one meant the need to invest a new Knight of the Garter, or "KG". This was the highest possible honor the Queen could bestow.

The "Queen of the Fairies" speech to the elves and fairies in the The Merry Wives of Windsor directly concerns heraldic aspects of the Knights of the Garter. In the final act of the play we read the following words:

Queen: About, about:

Search Windsor Castle (Elues) within, and out.

Strew good lucke (Ouphes) on euery sacred roome,

That it may stand till the perpetuall doome,

In state as wholsome, as in state 'tis fit,

Worthy the Owner, and the Owner it.

The seuerall Chaires of Order, looke you scowre

With iuyce of Balme; and euery precious flowre,

Each faire Instalment, Coate, and seu'rall Crest,

With loyall Blazon, euermore be blest.

And Nightly-meadow-Fairies, looke you sing

Like to the Garters-Compasse, in a ring

Th' expressure that it beares: Greene let it be,

More fertile-fresh then all the Field to see:

And, Hony Soit Qui Mal-y-Pence, write

In Emrold-tuffes, Flowres purple, blew, and white,

Like Saphire-pearle, and rich embroiderie,

Buckled below faire Knight-hoods bending knee;

Fairies vse Flowres for their characterie.Act V scene v (First Folio text, italics as in original)

The fairies and elves are consecrating Windsor castle and, in particular,

St George's Chapel, for this is the part of Windsor Castle concerned with

the Knights of the Garter ceremonial. In the chapel, each Knight of the

Garter is allotted a stall ("faire Instalment") in which is displayed

his banner ("loyal blazon") bearing his coat of arms ("Coate"), and his

helmet sporting his distinctive crest ("Crest"). The French phrase Hony

Soit Qui Mal-y-Pence is on the garter itself ("Buckled below faire

Knight-hoods bending knee").

(The French Hony

Soit Qui Mal-y-Pence means roughly "evil be to whom who thinks bad of

it" or "Evil to him who thinks evil", a saying with no clear traditional

source.)

In addition, much of the action in The Merry Wives of

Windsor takes place in a tavern called

"The Garter".

The fairies and elves are consecrating Windsor castle and, in particular,

St George's Chapel, for this is the part of Windsor Castle concerned with

the Knights of the Garter ceremonial. In the chapel, each Knight of the

Garter is allotted a stall ("faire Instalment") in which is displayed

his banner ("loyal blazon") bearing his coat of arms ("Coate"), and his

helmet sporting his distinctive crest ("Crest"). The French phrase Hony

Soit Qui Mal-y-Pence is on the garter itself ("Buckled below faire

Knight-hoods bending knee").

(The French Hony

Soit Qui Mal-y-Pence means roughly "evil be to whom who thinks bad of

it" or "Evil to him who thinks evil", a saying with no clear traditional

source.)

In addition, much of the action in The Merry Wives of

Windsor takes place in a tavern called

"The Garter".

During the period in question (1601-1602), only two new Knights of the Garter were invested, both in 1601: Thomas Cecil (2nd Lord Burghley), and William Stanley (Sixth Earl of Derby). There were no investitures in either 1600 or 1602. On May 26, 1601, William Stanley, presumably on "bending knee", was invested as a Knight of the Garter at Windsor Castle. The Merry Wives of Windsor first appears in history with the licensing of this play, about the investiture of the garter, in 1601 [2]. It would not be the first time a Shake-speare play was written for a ceremony involving William Stanley. It also happened for the marriage of William Stanley and Elizabeth de Vere with A Midsummer Night's Dream (see below).

An indication that Shake-speare himself was a Knight of the Garter comes from a reference in the play Histriomastix, revised by John Marston:

Enter Troylus and Cressida

Troy:

Come Cressida, my cresset light,

Thy face doth shine both day and night,

Behold, behold, thy garter blue

missing line

Thy knight his valiant elboe wears

that When he shakes his furious Speare

The foe in shivering fearfull sort,

may lay him down in death to snort.Cres:

O knight with valour in thy face,

here take my skreene wear it for grace,

Within thy Helmet put the same

Therewith to make thine enemies lame.

Landulpho:

Lame stuff indeed the like was never heard

Beyond the obvious reference to Shake-speare's Troilus and Cressida, we have a reference to "shakes his furious Speare", "knight", and "thy garter blue". The garter of the Knight of the Garter was blue. (The "valiant elboe" may refer to the fact that the "Lady"—William Stanley's wife it would be in this case— of the Knight of the Garter wore one near her elbow.) [3]

Marston certainly knew Derby—he was for some time the playwright for the Children of Paul's, an acting company of children supported by Derby (see Shakespearian Acting Companies , by Andrew Gurr). It is significant that no other candidates were ever Knights of the Garter. [4]

In addition to both the association of the play with a legal action involving the Earl of Derby, and his investiture as a Knight of the Garter, there is a final suggestive note to add concerning The Merry Wives of Windsor. The Quarto edition seems to to refer to Derby's neighbor Proctor himself in a word-play with a reference to "Proctors", a word for attorneys. The following line disappeared when the play was published in the First Folio (and the suit had been long resolved):

Goe laie the Proctors in the street

This is additional reason to suspect the Quarto edition was published without the author's cooperation, as the plays of Shake-speare are notable for their lack of personal attacks. Just as an earlier uncomplimentary association of Sir John Oldcastle (portrayed as Falstaff) was removed in deference to his surviving heirs in Henry IV, so here we find the specific reference to Proctor ultimately removed.

I now find that "In 1604, Sir Stephen Proctor was employed by Earl William in making long leases on the Stanley estates in Yorkshire" [5]. This appears to be a fine example of a forgive-and-forget attitude we might expect of a Shake-speare.

There is good reason to believe that this play was first performed for Derby's wedding, and this is a leading theory among Stratfordians and others. I had a discussion of this relative to the moon phase information given in the play itself but find it to need work at best, so nothng more here for now.

As is well-known, Shake-speare drew from the historians Hall and Holinshed, and his histories, allowing for dramatic license, often closely follow the texts. Of course, just like the histories, and indeed Elizabethan times in general, there is an emphasis on and justification of the foundation of the Tudor dynasty. But a Lancastrian bias has also been noticed, and it has long been noted by Derbyites, and more recently by some Stratfordians [1], that there is a Stanley family bias as well.

In chronological order of their subject matter, the history plays are:

King John

Richard II

1 Henry IV

2 Henry IV

Henry V

1 Henry VI

2 Henry VI

3 Henry VI

Richard III

Henry VIII

The period covered by the eight plays from Richard II through Richard III is more-or-less contiguous. The events described in King John took place long before, and those in Henry VIII considerably later.

Shake-speare did not write the plays in the same order that the events they cover unfolded. Although the exact order in which they were written has been disputed, it is universally agreed, for example, that the Henry VI plays were written before the Henry IV plays. It is likely that Shake-speare began with the intention of chronicling the rise of the Tudor dynasty, beginning with the protracted struggle between the houses of York and Lancaster known as the War of the Roses. These events are dramatized in his Henry VI plays. This was followed almost immediately by that crucial play of dynastic succession, Richard III, which culminates in the establishment of the Tudors. He then further explored the roots of these histories by writing Richard II, Henry IV, and then Henry V. King John was probably written sometime during the earlier period and Henry VIII was one of his last plays.

A plausible timeline of when they were written looks like this:

| Play | Year |

|---|---|

| King John | 1590-1595 |

| Henry VI, Part 1 | 1590-1592 |

| Henry VI, Part 2 | 1591 |

| Henry VI, Part 3 | 1592 |

| Richard III | 1593 |

| Richard II | 1595 |

| Henry IV, Part 1 | 1596 |

| Henry IV, Part 2 | 1597 |

| Henry V | 1599 |

| Henry VIII | 1613 |

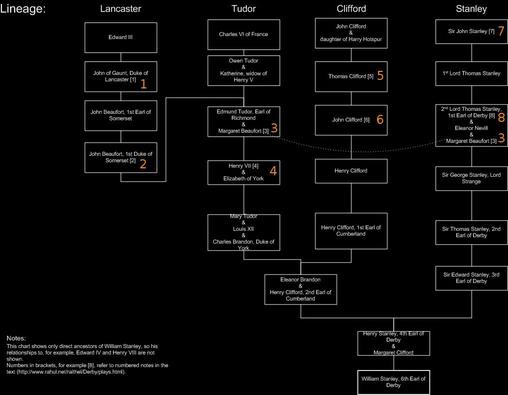

A study of the history plays with a chart of William Stanley's lineage proves enlightening. (Click on the chart below to view a larger version.)

The chart is selective and not meant as a general William Stanley genealogy, nor is it inclusive of all the many historical personages related to William Stanley that are mentioned in the plays. It only shows direct ancestors of William Stanley that appear in the plays, and should make clear how these central figures in the plays relate directly to him. No other candidates have family involved in the plays other than superficially. In fact, with the exception of royalty, no family line appears in the plays nearly as much as Stanley's.

What implicates Stanley as author even more, as we will see, is the way his direct ancestors are portrayed n the plays, a portrayal consistent with the theory that Will Derby was Shake-speare.

The notes below refer to the numbers shown in the chart:

"Shakespeare makes of this enormously powerful and wealthy man a patriotic and patriarchal figure of great probity and dignity: he is 'old John of Gaunt, time-honored Lancaster.' In this the playwright departs from his source Holinshed, who, with far greater historical accuracy, depicts Gaunt as a contentious and ambitious baron."Indeed, there is no known source for Shake-speare's portrayal of John of Gaunt as the wise sage. Perhaps it was a Stanley family tradition. If not, it would no doubt become one.

It is in John of Gaunt's mouth that Shake-speare puts his famous praise of England:

This royal throne of kings, this scept'red isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands;

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England

John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset -- In Henry VI, Part 1, John Beaufort, called "Somerset", is assigned the central symbolic role of the Lancastrian side of the War of the Roses when, during a quarrel in which York invites those who support him to pluck a white rose, Somerset plucks instead the red rose, forever to be associated with the side of Lancaster.

Margaret Beaufort -- Margaret Beaufort appears twice in the chart

(indicated by a dotted line) because she formed an early connection

between the house of Tudor and the Stanley family line by becoming the

2nd wife of Thomas Stanley after the death of Edmund Tudor. Henry VII,

therefore, was Thomas Stanley's stepson and this fact probably has much

to do with Thomas's eventual support of Henry Richmond both in history

and as portrayed in Richard III (discussed below). Margaret does

not appear as a character on the stage but is referred to as the Countess

of Richmond in Richard III.

Margaret Beaufort -- Margaret Beaufort appears twice in the chart

(indicated by a dotted line) because she formed an early connection

between the house of Tudor and the Stanley family line by becoming the

2nd wife of Thomas Stanley after the death of Edmund Tudor. Henry VII,

therefore, was Thomas Stanley's stepson and this fact probably has much

to do with Thomas's eventual support of Henry Richmond both in history

and as portrayed in Richard III (discussed below). Margaret does

not appear as a character on the stage but is referred to as the Countess

of Richmond in Richard III.

"[R III] did not, as Shakespeare asserts, imprison [Clarence, the heir presumptive], nor did he meanly match Clarence's daughter in marriage. It was left to HVII to do both these things and eventually to execute the boy on a trumped-up charge of treason."

It was certainly in the interest of the Stanley family to to portray Richard as unmitigated evil, given that Thomas and William Stanley betrayed him at Bosworth. Of course, it also looked better for the Tudors that Richard was portrayed as evil and Henry as good. Note that Richard's distrust (ultimately proved correct) of Thomas Stanley is not the author's invention, but historical.

Historically, Thomas Lord Clifford died on the Lancastrian side in the first battle of St. Albans, traditionally considered the first battle of the War of the Roses. In Henry VI, Part 2, Thomas Clifford's death is portrayed nobly and as directly at the hands of York when they meet on the battlefield:

CLIFFORD. What seest thou in me, York? Why dost thou pause?

YORK. With thy brave bearing should I be in love

But that thou art so fast mine enemy.

CLIFFORD. Nor should thy prowess want praise and esteem

But that 'tis shown ignobly and in treason.

YORK. So let it help me now against thy sword,

As I in justice and true right express it!

CLIFFORD. My soul and body on the action both!

YORK. A dreadful lay! Address thee instantly.

They fight and CLIFFORD falls

CLIFFORD. La fin couronne les oeuvres. Dies

YORK. Thus war hath given thee peace, for thou art still.

Peace with his soul, heaven, if it be thy will! Exit

This sets up the defining moment for the son of Thomas Clifford, John Clifford, when he comes upon the scene and discovers his dead father as discussed next.

Enter YOUNG CLIFFORD

YOUNG CLIFFORD. Shame and confusion! All is on the rout;

Fear frames disorder, and disorder wounds

Where it should guard. O war, thou son of hell,

Whom angry heavens do make their minister,

Throw in the frozen bosoms of our part

Hot coals of vengeance! Let no soldier fly.

He that is truly dedicate to war

Hath no self-love; nor he that loves himself

Hath not essentially, but by circumstance,

The name of valour. Sees his father's body

O, let the vile world end

And the premised flames of the last day

Knit earth and heaven together!

Now let the general trumpet blow his blast,

Particularities and petty sounds

To cease! Wast thou ordain'd, dear father,

To lose thy youth in peace and to achieve

The silver livery of advised age,

And in thy reverence and thy chair-days thus

To die in ruffian battle? Even at this sight

My heart is turn'd to stone; and while 'tis mine

It shall be stony. York not our old men spares;

No more will I their babes. Tears virginal

Shall be to me even as the dew to fire;

And beauty, that the tyrant oft reclaims,

Shall to my flaming wrath be oil and flax.

Henceforth I will not have to do with pity:

Meet I an infant of the house of York,

Into as many gobbets will I cut it

As wild Medea young Absyrtus did;

In cruelty will I seek out my fame.

Come, thou new ruin of old Clifford's house;

As did Aeneas old Anchises bear,

So bear I thee upon my manly shoulders;

But then Aeneas bare a living load,

Nothing so heavy as these woes of mine. Exit with the body

Of all the direct ancestors of Will Derby that appear in the plays, John Clifford is the only one I find that might be considered to have a villainous role. True to his vow above that "York not our old men spares; No more will I their babes" he murders York's young son Rutland in a pathetic scene in which the boy pleads for his life, and later participates in the humiliation and murder of York. Young Clifford dies with an arrow through his neck, and his head is placed on the gates of York, so concluding his role in this play so full of the bloody revenge of both sides in the War of the Roses.

DUCHESS

Art thou gone too? All comfort go with thee!

For none abides with me. My joy is death-

Death, at whose name I oft have been afeard,

Because I wish'd this world's eternity.

Stanley, I prithee go, and take me hence;

I care not whither, for I beg no favour,

Only convey me where thou art commanded.

STANLEY

Why, madam, that is to the Isle of Man,

There to be us'd according to your state.

DUCHESS

That's bad enough, for I am but reproach-

And shall I then be us'd reproachfully?

STANLEY

Like to a duchess and Duke Humphrey's lady;

According to that state you shall be us'd.

It is interesting to note that it has recently been proposed [2] that the charge of sorcery against the Duchess, as Shake-speare presents it in the play, may have been modeled after the charge that was made against William Stanley's mother, for the specific purpose of alluding to the fact that the charge against his mother was not treason.

Lord Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby -- Thomas Stanley was

created the 1st Earl of Derby by Henry VII as a direct result of the

role he played in the founding of the Tudor dynasty. This role is

dramatized in Shake-speare's Richard III.

Lord Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby -- Thomas Stanley was

created the 1st Earl of Derby by Henry VII as a direct result of the

role he played in the founding of the Tudor dynasty. This role is

dramatized in Shake-speare's Richard III.

Regarding Thomas Stanley, the 1st Earl of Derby, as he appears in Richard III, E. A. J. Honigmann says in Shakespeare, The Lost Years:

"Shakespeare rearranged history so as to make Stanley's services to the incoming Tudor dynasty seem more momentous than they really were."

Although you'd never know it from the play, historically, it was John de Vere the Earl of Oxford's forces that primarily engaged Richard on behalf of Henry Richmond at Bosworth. Sir William (not Thomas) Stanley's forces then decisively entered the battle during Richard's last desperate attempt to reach Henry, and then defeated Richard. Then, as in the play, Lord Thomas Stanley placed the crown on Richmond's, now Henry VII's, head. The play Richard III, however, subtly alters things. Sir William Stanley does not appear—he may be simply combined with Lord Thomas Stanley for dramatic reasons, but it is noteworthy that our William Stanley descends directly from Thomas Stanley, not William. Oxford, incidentally, has only two lines in the play and doesn't figure in the action at all. Bacon's history of Henry VII, contrary to Holinshed and Shake-speare, has Sir William Stanley crowning Henry [3].

In the play, Lord Thomas Stanley (called variously "Stanley" or "Derby" although he does not historically become the Earl of Derby until after the events described) plucks the crown from the dead Richard and then, consistent with Holinshed's history, places it on Henry's head. This moment is the founding of the Tudor dynasty, which continued until the death of Elizabeth I. In the play, Henry's first words as king are to invoke God and inquire after Lord Thomas Stanley's son who had been held hostage by Richard:

DERBY

Courageous Richmond, well hast thou acquit thee!

Lo, here, this long-usurped royalty

From the dead temples of this bloody wretch

Have I pluck'd off, to grace thy brows withal.

Wear it, enjoy it, and make much of it.

RICHMOND

Great God of heaven, say Amen to all!

But, tell me is young George Stanley living.

DERBY

He is, my lord, and safe in Leicester town,

Whither, if it please you, we may now withdraw us.

RICHMOND

What men of name are slain on either side?

QUEEN. Believe me, lords, for flying at the brook,

I saw not better sport these seven years' day;

Yet, by your leave, the wind was very high,

And ten to one old Joan had not gone out.

KING HENRY. But what a point, my lord, your falcon made,

And what a pitch she flew above the rest!

To see how God in all His creatures works!

Yea, man and birds are fain of climbing high.

SUFFOLK. No marvel, an it like your Majesty,

My Lord Protector's hawks do tow'r so well;

They know their master loves to be aloft,

And bears his thoughts above his falcon's pitch.

GLOUCESTER. My lord, 'tis but a base ignoble mind

That mounts no higher than a bird can soar.

Much of the language has to do with the technical terminology of falconry, apparently second nature to the poet.

The Derbyite case for William Stanley's authorship of Love's Labour's Lost is based on the ideas that, first, the events of the play almost certainly concern events in France that took place in the late 1570s, just before William Stanley would have been on the scene and, second, the appearance in the play of a caricature of William Stanley's tutor at this very time.

Abel Lefranc, a French professor of literary history first documented the strong parallels between events at the Court of Navarre in France and Love's Labour's Lost [1]. It is likely, but not proven, that Stanley was at the court in Navarre at Nerac near the time the events took place. William Stanley began his travels in France in 1582, when he was in his early twenties.

While there is a strong possibility that the author of Love's Labour's Lost had an intimate knowledge of the people and events at Navarre [2], this does not help us reduce the authorship possibilities much, as both Bacon and Oxford can be seen in association as well as William Stanley. What helps us narrow it down to William Stanley in particular is the character of Holofernes.

In 1584, two years after he and William Stanley went to France, Richard Lloyd published a play, with the title, in part, A brief discourse of the most renowned actes and right valiant conquests of these puisant Princes, called the Nine Worthies. The nearly 1200 lines of verse written by Lloyd can be shown to have many similarities to the masque in Love's Labour's Lost. For example, In Lloyd's Nine Worthies we find the following description of one of the worthies, Alexander the Great:

This puissant prince and conqueror bare in his shield a Lyon or,In the masque in Love's Labour's Lost, we find the following repartee from Costard to Sir Nathaniel interrupting the declarations of Alexander:

Wich sitting in a chaire bent a battel axe in his paw argent.

O, Sir, you have overthrown AlisanderA poleaxe is a battle axe but, instead of a chair, Shake-speare substitutes a close-stool, that is a stool containing a chamber pot, the forerunner of the water closet or flush toilet.

the conqueror! You will be scrap'd out of the painted cloth for

this. Your lion, that holds his poleaxe sitting on a close-stool,

will be given to Ajax. He will be the ninth Worthy. A conqueror

and afeard to speak! Run away for shame, Alisander.

But who is Richard Lloyd, and why in the world would Shake-speare make fun of such an obscure publication? Richard Lloyd was no less than William Stanley's tutor, and his chaperone on the intial stages of his journey abroad, leaving England for France with William in 1582. In Love's Labour's Lost, the Nine Worthies is produced by Holofernes, a name taken from Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel, where Holofernes is Gargantua's tutor.

It takes very little imagination to see the young William Stanley chafing under the control of Richard Lloyd, and poking a little harmless fun at him. It is interesting to ponder on the likelihood that Richard Lloyd may have in fact produced this play at Navarre, with perhaps not dissimilar results to those described in the play.

As for The Nine Worthies produced at Chester, the influence is more structural as, for example, in the conclusions of both the Chester performance and the performance in Love's Labour's Lost where declarations are made by the seasons of the year. In the Chester pageant they are Ver, OEstas, Autum, and Hiems, while Love's Labour's Lost includes just two, "Hiems, Winter; Ver, this Spring".

And what do the Stratfordians have to say about the source of the character Holofernes? The arguments are weak, but perhaps their leading proposal is that Holofernes is based on the great scholar John Florio, and includes such arguments as the fact that "I. HOLOFERNES" is a near anagram of "IOHNES FLOREO" [4]. Is Shake-speare supposed to have searched the available literature until he found a fictional character whose name, once he had anagrammed it, could be worked into something close to a latinized version of Florio's name? Attention is also drawn to the fact that Florio was a translator and grammarian of Italian, and Holofernes uses Italian expressions. What seems to be ignored is that, other than English of course, Holofernes mainly uses Latin expressions, and Lloyd peppered his writings with the same. Finally, why Shake-speare would make fun of the well-regarded John Florio is unclear at best.

As an example of how identifying the wrong man as Shake-speare could lead to further misidentifications, a Stratfordian, in his dismissal of the Derbyite case of Lloyd as Holofernes, said "Richard Lloyd is too obscure a figure in the national affairs of the country to be noted in a satire that includes the King of France and his courtiers" [5]. In other words, since Shakspur was Shake-speare, the identification makes no sense. Circular reasoning. At least he recognizes that the characters in the play do in fact refer to Henry and his courtiers, an admission that is difficult for many Stratfordians who recognize the problem of an upstart commoner of an author portraying living French nobility on the stage.

Shake-speare's knowledge of esoteric tradition is a highly sophisticated one, one that weaves through his sonnets and plays to a degree that is surprisingly under-investigated, possibly due to the desire to see Shake-speare as a forerunner of the scientific revolution, rather than as a man much more concerned with magical and occult sympathies. Few pursuits have been more fruitless than trying to find early scientific leanings in the works of Shake-speare. Shake-speare was decidedly not scientific, in an age when figures such as Francis Bacon were first giving clear evidence of the scientific shape of things to come.

A scholar of the Elizabethan occult [3] had this to say about the general naivete of Shake-speare scholars regarding these subjects:

[T]he typical English-speaking literary scholar [...] is unlikely (I suppose) to realize vividly, along his bones as it were, the extent and intensity of the Renaissance interest in occulta. For example, because he has not read widely in the discussion of daemons (and why should he be expected to have done so?) he may believe that Ariel and Caliban, in The Tempest, like the Earth-Spirit in Shelley's Prometheus Unbound, are poetic inventions which no contemporary reader or spectator could have imagined to be anything else. Again, he may take it for granted that Prospero's magic, for Shakespeare and the more knowing persons in his audience, was an immediately transparent metaphor for aesthetic creativity and that except for some especially raw yokel the fairies in Midsummer Night's Dream were fanciful borrowings from an exploded folklore.As usual, Shake-speare does not require one to understand his finer meaning, but to one who knows it is there, it adds life to otherwise mundane analogies.

It is commonly stated that astrological/alchemical views were a commonplace of the time—indeed, the scholar quoted above thought so. This mistaken idea may largely derive from the disproportionate influence Shake-speare himself has had on our picture of the English Renaissance. One has only to read Sydney's sonnets or Jonson's plays to get a more accurate picture of the influence, or rather lack of influence, of esoteric ideas in the Elizabethan age. (This is not to be confused with superstition which was prevalent then as now.)

Shake-speare was deeply imbued with what I will here call the "magical", by which I mean all kinds of astrological, alchemical, hermetic, and "Rosicrucian-like" lore. While such magical tendencies are perhaps most obvious in the late plays and particularly The Tempest, in fact they lace his work, and an understanding of basic occult lore aids in an understanding of the works. For example, here is the beautiful Sonnet 33:

Full many a glorious morning have I seen,I have read some tortured "explanations" of this sonnet, but I think it is straightforward, given some knowledge of then widespread, although often hidden, currents of thought. Shake-speare is using the idea of "correspondences", in which earthly phenomena are related to the heavens, as the logical structure of this sonnet. In particular, macrocosmic heavenly phenomena are paralleled by microcosmic human ones.

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green;

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy:

Anon permit the basest clouds to ride,

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine,

With all triumphant splendour on my brow,

But out alack, he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath masked him from me now.Yet him for this, my love no whit disdaineth,

Suns of the world may stain, when heaven's sun staineth.

While sonnet 33 may be many things besides, it is most definitely describing a macrocosmos-microcosmos relationship, the microcosmos in this case being the author himself. The one-hour emergence of his Sun refers to the microcosmic equivalent of the Sun in man, and the obscuring region cloud refers to the influence of the other planets within him. This psychological relationship of human beings to their spiritual Sun is a central image of esoteric teachings of Shake-speare's time. As Arthur Versluis [4] put it, commenting on the esoteric ideas of Shake-speare's contemporary Jacob Boehme:

[Boehme's] primary insight is into the necessity that the soul break through this astral "cloud" and hold to its origin in the divine light.

Or, take Sonnet 15, which is explicit regarding astrological influence:

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment.

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment.

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky:

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory.

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay,

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

Here we have Shake-speare referring to the celestial influences as the "secret influence" controlling what he so often represented life as: a play ("shows") with the world as a stage. The sonnet as a whole seems to end oddly if, as commonly supposed, Shake-speare is addressing some male or female lover. How could he possibly "engraft [them] new"? I suggest he was discussing something else entirely, something to do with regeneration in the esoteric sense. In fact, this regeneration may be described as the emergence of the Sun in man.

But all this seems fanciful to those who are not attracted to such ideas, and I suspect it was just such ideas that Oxford referred to when he mentioned Derby's "fancies". But to those who are attracted to such ideas, they occupy the center-stage of one's life, and one quickly learns to mask one's real interests in the face of society's lack of understanding, a lack that often leads to at least suspicion and ridicule.

There are very many references to astrological notions in Shake-speare's plays, so many that it is obvious that the influence of the planets was never far from his mind. For example, starting alphabetically by play:

All's Well That Ends Well

...that we, the poorer born,and

Whose baser stars do shut us up in wishes,

HELENA. Monsieur Parolles, you were born under a charitable star.etc.

PAROLLES. Under Mars, I.

Antony and Cleopatra

When my good stars, that were my former guides,and

that our stars,

Unreconciliable, should divide

Our equalness to this.

Cymbeline

Our Jovial star reign'd at his birth, ...

And so on, throughout the plays.

But there are very many esoteric currents in Shake-speare's work, and these are rarely even recognized. For example, in 1 Henry IV, the association of Hal with Mercury ("like feathered Mercury"), and the nature of his relationships with the jovial Falstaff and martial Hotspur ("Mars in swathling clothes") evidence a sophisticated knowledge of a little-known scheme of planetary types. In The Winter's Tale the statue of Hermione—a name derived from Hermes—comes to life, just as the Hermetic Asclepius described as being done in Egyptian magic. Esoteric currents present such problems that the Oxfordian Looney, on reading the following in The Tempest:

We are such stuffwas forced to conclude that The Tempest was not written by Shake-speare, because he couldn't understand it [5]. In this case, Shake-speare is referring to the ancient doctrine that mankind is asleep, also available in the Hermetic teaching.

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

While missing many such references to occult knowledge, some people do believe Shake-speare was addressing a particular occult school when he wrote the following in Love's Labour's Lost:

KING. O paradox! Black is the badge of hell,There is no definite evidence for this association, but it is an attempt to find a reference in Shake-speare to what may have been a particular circle of students of the occult, and we will see that that particular circle touches closely on the life of William Stanley.

The hue of dungeons, and the school of night;

And beauty's crest becomes the heavens well.

That Shake-speare's plays are full of magicians, witches, ghosts, fairies, and other such characters will surprise no one, but unlike the general tenor of the time, Shake-speare's magical creations were often white magic, as opposed to black magic, in that they "genuinely" effected good, not evil or the mere fakery of the charlatan. In As You Like It we hear Rosalind say:

I have, since I was three year old, convers'd with a magician, most profound in his art and yet not damnable.Cerimon, in Pericles is another example of the good magician. And, of course, it is in The Tempest that we find that most powerful of good magicians, Prospero.

Shake-speare's non-condemning attittude toward magic and occult philosophy is especially notable in light of the different attitude displayed by other playwrights of his time. Marlowe, Jonson, and Greene, for example, ridiculed or condemned such interests, focusing on the inevitable charlatans associated with such ideas. Where the magicians are not charlatans, they are almost invariably "black" magicians that are made to suffer for their actions at the end of the play. Prospero in The Tempest has a very different role. As Dame Francis Yates recently put it: "Shakespeare's conjuror, Prospero, is noble and beneficient; Jonson's Subtle, the alchemist, is a charlatan and a cheat. Yet both are drawn from Doctor Dee."[6]

We know that William Stanley was exposed to the occult sciences from his childhood on. Tantalizing references to a "zodiacal screen" in the main hall of the house at Lathom indicate a large-scale display that was updated daily to show the positions of the planets. The screen was created by order of William Stanley's mother, Margaret, about whom we read:

William Camden described her as having 'a womanish curiosity' constantly prying into the future. By 1580, apparently distracted by rheumatic pain as well as marital unhappiness, she had begun to seek relief in the advice and remedies of 'wizards and cunning men'. In some distress she wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham that the charges against her of meddling in black magic 'doth more vex my heart and spirit than ever any infirmyties have done my body', but in that credulous age it was easy to acquire, and difficult to lose, a reputation for witchcraft. In 1580, the Queen took the charges seriously enough to restrict Margaret's freedom to such an extent that she could complain of hardship suffered as 'her majesty's prisoner'. Possibly Elizabeth shared Camden's suspicions that Margaret, a grand-niece of Henry VIII [and great grand-daughter of Henry VII], had consulted her wizards 'with a vain credulity and out of I know not what ambitious hope'. Elizabeth disapproved of nothing more strongly than speculation concerning the royal succession.(That "speculation concerning the royal succession" was, of course, not idle curiosity. The question was if the royal succession applied to her then-living first son Ferdinando, William Stanley's older brother.)

The Earls of Derby, J. J. Bagley

The fact that this "zodiacal screen", or planetarium, existed in the main hall at Lathom and that Lathom was a scene of frequent theatricals, has led one writer [7] to suggest the interesting possibility that this is the origin of the painting of the heavens that began to appear on the roof above the playhouse stage in Elizabethan theaters (appropriately called "The Heavens") and referred to in plays as, for example, when Lorenzo, in The Merchant of Venice, presumably gesturing upwards, says:

Sit, Jessica. Look how the floor of heavenThis refers to the Pythagorean "harmony of the spheres".

Is thick inlaid with patines of bright gold;

There's not the smallest orb which thou behold'st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still quiring to the young-ey'd cherubins;

Such harmony is in immortal souls...

We also know that other members of William's immediate family were deeply imbued with the sense of the magical. In 1594, George Chapman published his Shadow of Night, in which he says the following in his dedication to Matthew Roydon:

I remember my good Mat. how joyfully oftentimes you reported unto me, that most ingenious Darbie, deepe searching Northumberland, and skill-embracing heire of Hunsdon had most profitably entertained learning in themselvesIt has been frequently proposed that the gentlemen mentioned may have been patrons of a "school of night" dedicated to alchemical pursuits and the psychological practices of the "art of melancholy". That "ingenious Darbie" refers to the Earl of Derby is clear. What is not clear is which Earl of Derby. It is either Henry, the fourth Earl, Ferdinando the fifth Earl, or William the sixth Earl. Henry had been Earl up until his death in late 1593. Ferdinando then became Earl until his death in mid-1594, at which time William became Earl. Assuming it is not William himself that is being referred to, the dedication clearly associates a close family member as involved with these alchemists who include "deep searching Northumberland", also known as "the wizard Earl".

That William's brother Ferdinando was immersed in a magical outlook is evident from the details surrounding his last days in which he ascribed his deteriorating condition to witchcraft (not poisoning, as is generally accepted today). Even more curious is a reference to Ferdinando as "Amyntas" by Nashe, as "thou, most curteous Amyntas, be the second mistical argument of the Knight of the Red-Crosse" (Pierce Penniless, Thomas Nashe). This inevitably suggests the Rosy-Cross knights, or Rosicrucians, which at first seems mere coincidence, as the Rosicrucian label arose later, in 1614, and in Germany. But Yates [8] has done a lot of work showing the connection between John Dee and what later became the Rosicrusian literature, and the likelihood of an Elizabethan English origin of the "Rosicrucian Enlightenment".

Furthermore, we learn that the author of the original Rosicrucian manifesto first wrote works inspired by English actors he had seen (Yates), and that regarding a magical practice of conversing with spirits "in England it was conserved there by tradition in certain illustrious families" [9].

John Dee, like Shake-speare, was familiar with various occult studies, including Rosicrucian-like leanings and alchemical and astrological ideas. Dee was a kind of Magus in aristocratic Elizabethan circles, a familiar with the Queen as well as much of the nobility. The record of the relationship between Dee and Derby is based almost entirely on the fragmentary remaining portions of Dee's journal. How they met is uncertain, although a report of Derby's life has them meeting in Moscow, when both Dee and Derby were abroad.

That they met and were friends is undeniable. Dee records a number of meetings with Derby, the date and time of William's daughter's birth, and added the occasional report of Derby's doings, including visits, in his diary. And Derby was instrumental in getting Dee appointed director of Christ's College, Manchester.

[O]f all the plays, The Tempest is the most deceptively simple, for it is the most profound. Appearing to be a mere comedy, a tale for entertainment's sake, it is in fact the culmination of all Shakespeare's dramas, for in it are not only the most beautiful lines in all the dramas, but the most profound of implications as well. In it we see the esoteric path to the restoration of order, of primoridal balance in the cosmos; in it we see the path back to Eden, the possibility of human self-mastery and self-transcendence. One cannot exhaust its meanings.Shakespeare the Magus, Arthur Versluis

It is widely believed that The Tempest was Shake-speare's farewell to the theater and that the epilogue may be read as such:

Now my charms are all o'erthrown,

And what strength I have's mine own,

Which is most faint. Now 'tis true,

I must be here confin'd by you,

Or sent to Naples. Let me not,

Since I have my dukedom got,

And pardon'd the deceiver, dwell

In this bare island by your spell;

But release me from my bands

With the help of your good hands.

Gentle breath of yours my sails

Must fill, or else my project fails,

Which was to please. Now I want

Spirits to enforce, art to enchant;

And my ending is despair

Unless I be reliev'd by prayer,

Which pierces so that it assaults

Mercy itself, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon'd be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

We know of no public performances of The Tempest before its publication as the first play in the First Folio, in 1623. The play had, however, been presented at court on Hallowmass Night, November 1, 1611.

As the Riverside Shakespeare puts it:

It must have been a fairly new play then, because it draws on some travel accounts which were not available in England before the autumn of 1610. A date of composition can then be more definitely fixed for The Tempest than for most plays of Shakespeare.

The period of time in which The Tempest is believed to have been written, 1610/1611, is very significant in the life of William Stanley. For it is only with a private Act of Parliament in 1610 that the final piece of the great lawsuit that had constrained the Earl's resources for 15 years was finally brought to a close. This final resolution granted the Earl the Isle of Man.

I believe that, metaphorically, The Tempest reflects the story of the division and restoration of the Stanley family inheritance. The division is represented by Miranda on William Stanley's side, who is 15 years old and soon to be married to Ferdinand, just as the division of the Stanley inheritance is healed at between 15 and 16 years after it began. The healing of the division with the other side in the law suit is represented by Miranda's marriage to Ferdinand, because William Stanley's brother Ferdinando caused the division with his death-bed attempt to transfer the inheritance to his wife.

I pray thee marke me, that a brother should be so perfidious: he whom next thy selfe of all the worlde I lov'd

Act I, Scene 2

With the restoration of his inheritance, Stanley began a gradual withdrawal from active affairs. This began in 1610 when he transferred control of the Isle of Man to his wife.

Fifteen years of unwelcome dispute and worry seemed to convince William that henceforward he must lead a more placid life consolidating the administration of his estates, earning the goodwill of neighbouring landowners, and indulging his personal interests in music and drama.Having finally attained what he had fought for, William relinquished control to his wife and, increasingly, his son James as James grew into his maturity. The divisions that had racked his inheritance had finally been resolved.

The Earls of Derby J. J. Bagley

[Prospero] differs from Roger Bolinbroke, Friar Camolet, and Landoffe in one major respect: his powers of magic are dedicated to his own rehabilitation and not to the political interests of a client." And "...he asks no more than what has been taken away from him."

The Occult on the Tudor and Stuart Stage, Robert Reed. [10].

The name Ariel may have been drawn from Dee's Uriel. While the name Ariel occurs in the bible, unlike Dee's Uriel, it has nothing to do with an active spirit agent. Specific powers of Ariel seem to have been derived from the character of Shrimp in Munday's The Book of John a Kent and John a Cumber, a manuscript of which survives, bound with portions of the same medieval document used in binding The Book of Sir Thomas More [10].

I don't know of any speculations on the origin of the name Prospero. But I have one. In Ben Jonson's much earlier Every Man In His Humour, there is a character Prospero, who is a carefree second son with an entitled older brother. Just as Derby was the second son, not expected to inherit the Earldom destined for his older brother Ferdinando. Could Derby have identified himself with this character in Jonson's play? (I note another parallelism between Jonson's Every Man In His Humour and Shake-speare's Tempest: in both there is an ineffectual fellow named Stephano.) [11] Jonson later revisited this play, anglicizing the location and names, and Prospero became the hyphenated "Well-bred". The behavior of this character may well reflect the strong temper and "prodigal courses" (see A Brief Life of William Stanley) of William Stanley.

The Tempest is the second play in which Shake-speare named a central noble character Ferdinand (the first being Love's Labour's Lost), a very similar name to William's dead brother, Ferdinando. In the first scene of The Tempest in fact, when "Ferdinand" enters the action, the First Folio has him as Ferdinando.

One source that has been plausibly identified as used by Shake-speare for The Tempest is a letter from William Strachey to an unidentified "Lady" dated July 15, 1610. The letter is believed to have been addressed to someone involved in the Virginia Company, and Strachey is writing concerning, among other things, a storm, shipwreck, and landfall that are clearly sources used in The Tempest. For details on this association, I refer you to David Kathman's Dating The Tempest on the Web.

Since Oxford died six years before this letter was written, he could not have written The Tempest. Since the letter was not published until 1625, and The Tempest written about 1611, the author must have had access to someone in the Virginia Company, and Stratfordians have put no little effort into identifying possible Shakspur connections. The Stratfordian's connections, as described by Kathman, may be summarized as:

Certainly none of this is impossible. Many, many people in London and the theater, however, could supply similar credentials. They all assume, too, that this letter was being passed around, or copied and distributed, etc, almost immediately after its arrival.

William Stanley, however, has a much stronger case. Strachey

appears to have been at Gray's Inn at the same time as Stanley.

They had a common friend in John Donne [12]. Strachey was a

"principal shareholder" [13] in Paul's Boys,

a childrens acting company supported by William Stanley.

That William Stanley had much better connections to

members of the Virginia Company is obvious simply because

the major investors were members of the aristocracy.

For example, The Third Virginia Charter March 12, 1612

(http://www.law.ou.edu/hist/vchart3.html) ends with a list of

332 contributors, here are the first 10:

George, Lord Archbishopp of Canterbury

Gilbert, Earle of Shrewsberry

Mary, Countesse of Shrewes-

Elizabeth, Countesse of Derby

Margarett, Countesse of Com-berland

Henry, Earle of Huntingdon

Edward, Earle of Beddford

Lucy, Countesse of Bedford

Marie, Countesse of Pembroke

Richard, Earle of Clanrickard

I don't think it would be difficult to find personal connections

between Will Derby and many Virginia Company principals. These

are Derby's peers. But especially interesting is the fourth

name on the list, "Elizabeth, Countesse of Derby", William

Stanley's wife.

"By curious chance a paper survives, noting that a copy of North's translation was borrowed from the library of Ferdinando Stanley; it was loaned to one "Wilhelmi" by Ferdinando's wife, Alice, and returned in 1611." [1]

Naturally, I think William Stanley borrowed this from his sister-in-law, while some Stratfordians believe this must evidence a close connection between Shakspur and Alice.

Notes on The Merry Wives of Windsor

Particulars concerning the garter ceremony can be found on the web, including http://www.heraldicsculptor.com/Garters.html. The page at http://www.heraldica.org/topics/orders/garterlist.htm is a list of all KG.

Notes on A Midsummer Night's Dream

Regarding Honigmann's book, I find that Alan C. Coman, a researcher of drama in Derby's backyard, has some interesting things to say. Coman has the following footnote relative to Shake-speare's Lancashire connection:

Prof E. A. J. Honigmann is the latest to argue this in Shakespeare: the 'lost years' (Manchester 1985). Though the case he makes for the necessity of Shakespeare's having become attached to Lord Strange's company is plausibly argued, the contortions he has to go through to equate William Shakeshafte with William Shakespeare are as bad as most of the cases made for the rival Shakespeare claimants, involving as they do the deliberate adoption of a pseudonym by an inconsequential Stratford boy for self-protection. His 'Shakespeare as Catholic recusant' premise also is very doubtful because my research shows clearly that Ferdinando Lord Strange, in the years in question, was a zealous prosecutor, not a protector, of Catholic recusants; indeed, he was commended by the Privy Council for his rigor and he strongly criticised his father's ambivalence in the matter. His zeal may have cost him his life. The irony mocking Prof Honigmann's whole attempt to explain how Shakespeare of Stratford could have acquired the patronage of Lord Strange and been Shakespeare the author, of course, is that William Stanley is already the one best placed to accomplish everything Honigmann wants Shakespeare to have been able to do. In this respect he has unwittingly done the Stanley/Derby/Shakespeare claimants a service.Alan C. Coman, "The Congleton accounts: further evidence of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama in Cheshire". Records of Early English Drama newsletter, Volume 14, Number 1, 1989.

Notes on the History Plays

My chief source on the history plays has been Shakespeare's English Kings: History, Chronicle, and Drama by Peter Saccio.

Notes on Love's Labour's Lost

There may be quite a lot of back and forth between Shake-speare and Jonson with The Tempest and Every Man in His Humour. In the Prologue to Every Man in His Humour, Jonson contrasts his more classical style with Shake-speare's, referencing other Shake-speare plays and then The Tempest in the following lines I've italicized:

... Nor nimble squib is seen to make afeard The gentlewomen; nor roll'd bullet heard To say, it thunders; nor tempestuous drum Rumbles, to tell you when the storm doth come; But deeds, and language, such as men do use, And persons, such as comedy would choose, When she would shew an image of the times, And sport with human follies, not with crimes. Except we make them such, by loving still Our popular errors, when we know they're ill. I mean such errors as you'll all confess, By laughing at them, they deserve no less: Which when you heartily do, there's hope left then, You, that have so grac'd monsters, may like men.

(This was pointed out in A Disquisition on the Scene, Origin, Date, Etc. Etc. of Shakespeare's Tempest, in a Letter by Joseph Hunter, 1839.) The Prologue was not in the 1601 Quarto, and first appeared in the 1616 Folio edition of Jonson's works.

Jonson may have felt a special need to distinguish his approach from Shake-speare's at this time, because Shake-speare had done Jonsonian things with The Tempest. The Folger edition notes:

The Tempest, unlike most of Shakespeare's plays, carefully observes the unities of time and place. Structurally, the play has some of the characteristics of the type of entertainment that Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones, the architect, were making popular at court.

And as the Riverside Shakespeare has it:

The play is unusual among the works of Shakespeare in that it follows the unities of time and place; only The Comedy of Errors is as compact.

and

Some critics say that in The Tempest Shakespeare was merely showing people like Ben Jonson that he could follow the unities if he wanted to.

Of course they are not saying he "merely" did that with The Tempest, just that he had in fact done that.

It is also interesting to note that Every Man in His Humour appears first in Jonson's Folio, and The Tempest first in Shake-speare's Folio.